What's the deal with cats and bird flu?

"How it's gotten to this point is mind boggling."

You are reading a post for paid subscribers. To continue receiving original reporting like this, please consider subscribing or upgrading to the paid tier of Tail Mail.

There’s no way to sugarcoat this: Chickens and dairy cows are getting sick with a bird flu virus that’s making its way into the pet food supply chain, leading to the infections and deaths of some household cats.

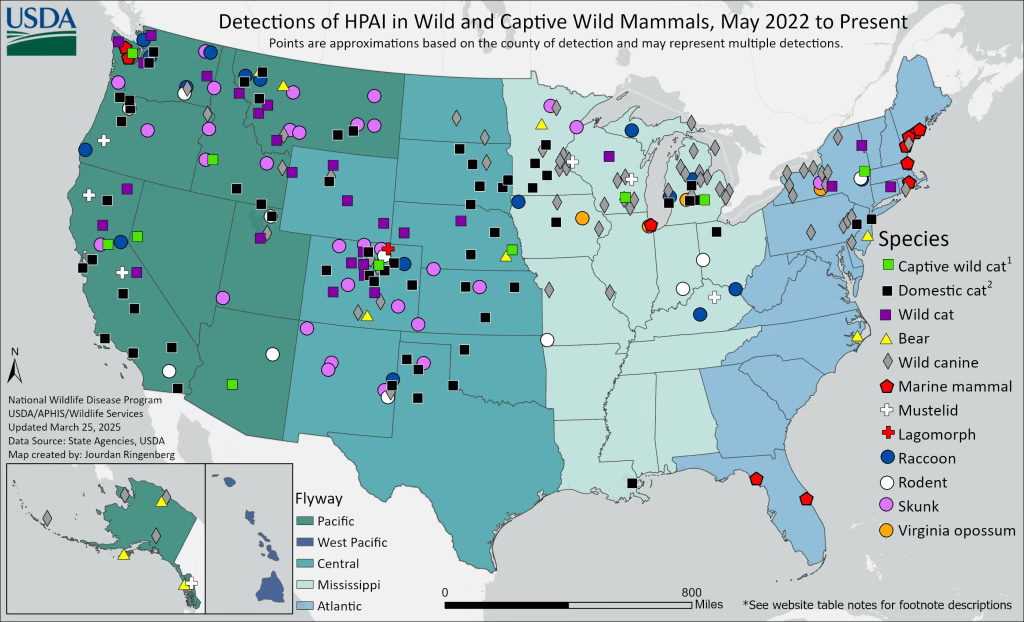

To be clear, the number of infections and fatalities represent just a small percentage of the roughly 73.8 million cats who live in the United States. But since late 2022, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has detected H5N1, or bird flu, in at least 126 domestic cats, with 62 of those detections occurring this year, raising concerns about the spread of the virus and its ability to mutate and infect other mammals.

Like the seasonal flu, bird flu is an airborne virus; humans can become infected by breathing infected respiratory droplets or by touching an infected surface and then touching their faces. Unlike the seasonal flu, bird flu is not highly contagious between humans. Instead, as the name suggests, it spreads quickly among birds and can wipe out an entire flock within days, resulting in major disruptions to the food supply chain (hence the expensive carton of eggs at the grocery store). Dairy cows have also become susceptible to bird flu and can spread the virus through their milk.

Of the known cases of cat infections, several of those cats had close contact to infected birds by living on a farm, eating raw prey, or drinking raw milk from infected dairy cows.

But much is still yet unknown about H5N1’s ability to mutate and impact mammals. Though the virus has been particularly fatal for infected cats, the USDA has not detected any H5N1 infections in household dogs to date, though wild red foxes—a member of the canine family—have become sick with the virus. Veterinarians working with cats have also been advised to take extra precautions and use personal protective equipment to lower the potential risk of human infection.

“For a period of about six weeks, every cat that came in, we stopped the owner and said, ‘Have you fed any raw milk or raw food products?’ Even if the cat was just there for vaccines or whatever and was totally fine, we were treating that patient as potentially infectious,” Dr. Christie Long, the chief medical officer at the veterinary chain Modern Animal, tells me.

The diagnosis process is not “easy,” according to Long. Symptoms may present as neurological, such as wobbliness or blindness, so some veterinarians may not immediately think of doing a respiratory PCR test to check for avian influenza. Cats also need to be checked in an isolated room that must be disinfected after each use, and it can sometimes take a whole week for a PCR test to come back to confirm a positive H5N1 infection.

For positive cases in household cats, treatment can be complex. Though cats have survived after being infected with bird flu, it has been fatal for others. There is currently no cure for bird flu, so vets may use a combination of antivirals, fluids, and other supportive treatments to help a cat.

“You have to have this very heightened sense of concern,” Long says. “We have to continue to do the best we can with the information we have, but it is just an … evolving thing.”